SCBWI is offering its members free digital workshops with industry experts and I've been specifically interested in those that deal with editing.

This one (I skipped the ones that dealt with illustrators or the business end of publishing, because I'm focusing on writing / editing techniques) was with Linda Sue Park. In it she detailed how she "Uses Scene to Build Story."

She cautioned, at the very beginning, that this system works for her, but it may not work for you (or me!). The way I see it, that's OK. I like to have many different evaluative tools in my toolbox when it comes to drafting and editing and revising, and if this one works, great.

I connected with it because I realized I'm using a similar approach to draft a page-1 rewrite of a MG novel I finished a while back, as opposed to heavy outlining, which I do for my mysteries and which seem much more complicated than this method can accommodate, to be honest.

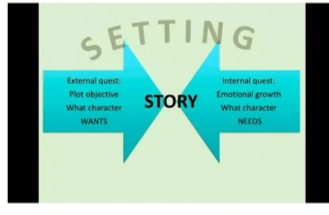

First of all, she boiled stories down to two elements -- an internal quest (what the character's needs), and an external quest (what the character wants). She pointed out that most of the time, characters don't know what they need at the beginning, so they're not actively thinking about their internal quests. That's natural. However, she said you should be able to articulate in two sentences or less, each of these, about your book.

So, her first evaluative tool: write two sentences about your MS. What is the character's external quest? What is the internal quest?

The next evaluation technique she took from screenwriting, specifically movies (!!YES!! I've been learning / using screenwriting techniques for a while now). She reiterated the screenwriting maxim that a scene has to be focused on something that's in motion, even if that motion is just the mouths of two people talking. If the camera stops on something completely static, no movement whatsoever, how long does it take before the audience gets restless? A couple of seconds, maybe 3-5.

To illustrate this, she used the following equivalencies:

- 1 minute of film = 2 pages of text

- 30 seconds of film = 1 page of text

- 15 seconds of film = half a page of text

Can you see why half a page of description or internal monologue is too long for the scene to go without having some movement, especially for younger readers? Do you see how quickly you can lose your reader? I'd add, generally speaking, the younger your reader, the fewer seconds are needed to lose them.

So, her second evaluative tool: use these film equivalencies to evaluate your MS.

How does she do this? She said she writes one sentence that encapsulates the movement of each scene. It's a one sentence summary of what's happening in the scene. Or, she suggested thinking about it as writing what's different /changed by the end of the scene.

If you can't write a single sentence that captures the movement, the action, the change that occurs because of that scene, then that scene has larger problems, and you may need to go back and figure out what the heart is.

Exercise 1:

Write a one-sentence summary of three scenes from your WIP. Then do that for the whole MS.

I can see other ways this evaluation could be done. You could go through the text, color-code for narration or internal dialogue and see where you're physically heavy (like, the amount of space on a printed page) on them, especially if beta readers or CPs say the story is slow going, difficult to get through, or they make the comment, "The action's picking up now," implying the action prior to this was slow. Often readers don't know why they feel the way they feel about a story, or they can't articulate what's causing them to feel that way. This is one tool you can whip out when a CP or beta points out a slow-going section to evaluate your story.

Her third evaluative tool: Determine if you have a good scene. What criteria do you use to do that?

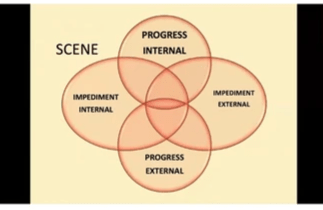

According to her, this (graphic below) is what constitutes a scene. If the scene lacks one of these elements, it may need to be rewritten. She emphasized that sometimes deciding to do nothing also constitutes "making a decision" and "taking action," especially when there are consequences.

She also, interestingly, said she varies the amount of time or space on the page that each scene spends in one of these four circles. For example, in some scenes, a character agonizes over circle one, what decision to make, and that's what the bulk of the text will dwell on. In other scenes, the character will make a snap decision and the action they decide to take is the focus of the text in the scene (the purple circle). She tries not to have too many scenes dwelling in the same circle in a row.

Again, I can see color-coding a text to figure out if you're repeating certain types of scenes too often. You could even keep her colors!

In addition, she also evaluates each scene for one of two criteria, which gets to her fourth evaluative tool: determine if the protagonist make progress toward a quest, or is the MC impeded in their desire to make progress on a quest?

Exercise 2: Classify every scene as either:

1. Progress

2. Impediment

She said this exercise is good for evaluating the balance of your MS. She said you want a combination of tension and satisfaction. If there are too many scenes in a row of impediment, the story might be getting too depressing or unsatisfying. But if there's too many scenes of progress in a row, the tension might be easing off too much. Either way, you risk losing the reader. You want a good mix of scenes.

After you've done that, she suggested going even deeper, which gets at her fifth evaluative tool: identifying which of the quests the scene either progresses toward or impedes. She said you aim for both, with the goal of hitting the "heart" of these overlapping quests, the very center of these four Venn diagrams.

She said this is often not the case when a CP or beta reader gives feedback, saying: "This story feels thin, feels flat, there's not enough depth to it." That's indicative of an absence of scenes that overlap in these areas.

She also pointed out that a plot development that seems at first to be progress, but turns out to be an impediment, is in the middle, or the "heart," of that diagram.

And I loved her next piece of advice for evaluating the audience of your MS. She said often the age of the protagonist does this for you, but questions come when authors have protagonists in that 12-14 in-between range.

One big difference between YA and MG was that in YA, there's pages and pages of internal impediment, whereas there's not so much in MG. YA has a greater emphasis on impediment than in most MG in general. Both should have a mix, but if your story is heavy on impediment, you're aging it up to YA. (I found this super-duper helpful!)

She writes MG, and her advice was that if she's writing / including internal monologue or static description at all, to try to limit it to one paragraph. She pointed out that in MG, readers are learning about other people by watching what they do and say. So wherever possible, she prefers action and movement to internal dialogue.

Exercise 3:

1. Go through your MS, scene by scene alongside this diagram.

2. Identify where on the diagram each scene is working.

3. Consider how to bring in some of these other things to get to the heart of that diagram, to add depth to your work.

She ended by talking about, apropos, endings, but I got the feel that could be the subject of a separate webinar. She said she aims for endings with a feel of "unexpected inevitablity." She said you want the reader to feel like this is the ending that had to happen, but it should also be a surprise. She works at planting clues along the way for the reader to subconsciously pick up on, so the ending feels like it has to be the ending of the story.

Thank you SCBWI, and thank you Linda Sue Park, for this free digital workshop on "Using Scene to Build Story."