SCBWI is offering its members free digital workshops with industry experts and I have been specifically interested in those that deal with editing.

The first digital workshop was with Kate Messner and she offered some amazing editing tips and insights.

This next one, with Sara Sargent, senior executive editor at Random House Children's Books, is the last part of that editing process.

But it's titled, "Outstanding Openers," you say? Don't you write the opening at the beginning? When you're drafting?

True, but this workshop, like the first, is focused on revision.

She talked specifically about making your first line / first page shine, but it's not something you do at the beginning of drafting, or even during the mid-editing / revision process.

She said it's the last thing she asks authors to do, to go back and rework or rewrite their first lines, first page, after completing all their other edits.

Her message resonated with me, because it was not until I finished DL, edited it several times, worked out all the kinks, even edited it from 121K to 84K, that I went back and totally stumbled on the 1st 5 Pages Writing Workshop. Since reworking my opening, I've gotten some interest in DL, with two requests so far -- ultimate passes, but still, the new opening has made all the difference, and it was almost the last thing I did with the story.

So, for my new WIP? Yeah, I have an opening. I love it. But I also recognize, when I'm still drafting, it's probably just a placeholder. Painful as that may be, that's what she's saying, essentially.

She started off by asking a simple but key question: What do you want your opening to accomplish? The first line / first page should pull the reader in, but implied in that is that the opening line, opening page will keep the reader reading to the next page. And that's it's purpose. It's that simple and yet so complex.

She offered seven (7) "Elements of a Good Beginning." She made a point of saying, you don't have to have all of these. Not having one or several in your opening is not "bad." It just is. You should diagnose your opening, figure out which of these elements you employ, which you want to have, which you don't want or don't really care about, and then focus on what you want to do well -- and upon revision, do it super-duper well.

Some of these terms / devices are self-explanatory, but they're all designed to get the reader to turn the page, and keep reading.

She gave examples of each and there were updated examples by authors / POC listed on the SCBWI web site, in case you're interested in employing Kate Messner's advice about using a "mentor text."

Sense of Intrigue -- The opening communicates that something is coming, it's a promise from the author to keep reading for something dramatic, exciting.

Sense of place -- She said this needs to bring an emotion with it, not be totally ordinary.

Compelling voice -- The character's voice is what will compel the reader to continue.

Tension -- There's a catalyst or a problem to solve. She did mention that tension is probably the most plot-driven opening, and includes seeds to a mystery. But it can be anything packed with meaning and implication.

Darn Good Writing -- Just that.

One Good Device -- An idea / an anchor device or structure around which the whole novel / character's journey is based. These can be treasure maps, letters, etc. that chart or mark the progression of the story / journey. The reader knows the author will keep coming back to these things, to show progression in the story.

Compelling Character -- It establishes that the reader can like / trust this character enough to want to keep reading. The character is honest, earnest, vulnerable, unzips their heart, you see all their insides.

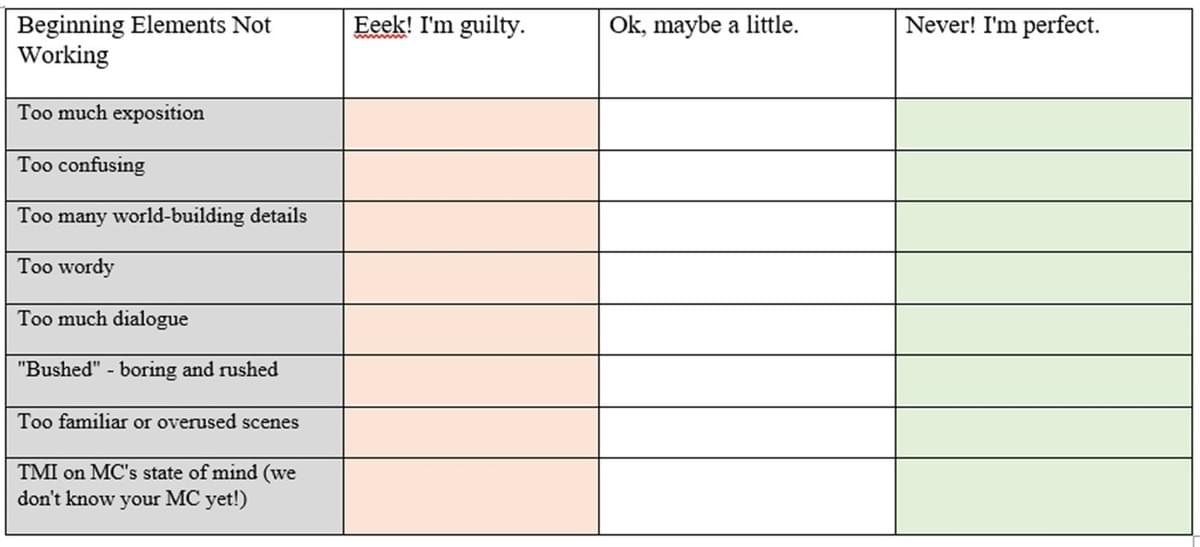

Once you've diagnosed your own MS, then take a look at "When Openings Don't Work" and diagnose your MS opening line / page for these qualities:

"Bushed," she said, implies you need to work on pacing. The overused / familiar scenes included waking up, seeing oneself in the mirror, 1st day of school, etc.

What do you do to fix these issues? After you've diagnosed your MS, here's what she recommended:

- Perfect the pacing of 1st line, 1st page, 1st chapter, throughout the book, so you're only giving the reader what's necessary, holding off on what can wait for later. She recommended reading the work out loud to help with this.

- Simplify.

- For speculative, genre fiction, she suggested making your terms clear, or at least put them into context (contextualize).

- Introduce fewer characters.

- Take one (1) calculated risk. Get a bit creative / artistic with it. Do something unique, different, something that leaves a mark.

She had other wonderful things to say about first lines / pages:

- Prologues are not all bad, but they need to be integral to the story. The book should not be able to function without it. It is the opening to your book. Use these criteria to evaluate it.

- World building shouldn't overwhelm the reader. It should feel natural, but give it to us slowly.

- If writing in a different historical time period, signal it. Your opening needs to locate us in time, as well as place. We should get a foothold for the rest of the book.

- Inciting incidents don't happen in the first line / first chapter. Wooohooooo!!!!!!!!!!!! Yeah!

- It's okay for stories that employ flashbacks / non-linear storylines to rely on a device -- a time / date / geographical stamp -- to alert the reader. "Day 1" or "May 4, 1967".

- Unlikable characters need some kernel, something that the reader can relate to and see themselves in.

- If you have multiple POVs, you shouldn't go more than two chapters in one POV before switching. In fact, later she said not to repeat a POV chapter until you've introduced all the POV characters. It's a matter of setting reader expectations.

- Deliver backstory -- but only what's absolutely necessary to understand the story -- in a tight, pacey, full of tension way.

- The POVs she leaned toward are 1st for YA, 3rd for MG.

- And interestingly enough, she said she won't read a QL (query letter) when reading pages. She gives a book the first few lines, maybe first 5 pages. If they don't deliver, she'll skip to the middle of the book, just to give it a chance, but...that's how fast she decides whether to keep reading.

Big take-away here: Your first line, first page, first five (5) pages are super-duper important, and you should revise them when you're finished, and have a really good grasp on what you want your opening to accomplish, not mid-way through revision.

Thank you SCBWI, and thank you Sara Sargent for this free digital workshop on outstanding openers.