Is my story MG or YA?

It's a question I see periodically in all my writing groups -- "I have a story about XYZ. My protagonist is 9 (or 10, 11, 12, 13). Is my story MG or YA?"

Authors want a quick answer.

But what they're really asking is, what makes a middle grade book middle grade, and what makes a YA story YA?

And that's not so easy to define. I'd say it comes down to two things: voice and themes.

But that's not the answer given in most of my writing groups. What gets spouted most often is "age of the protagonist."

Well, here are two stories that are excellent mentor texts for showing, definitively, that age of the protagonist is NOT the defining factor of the audience you're writing for.

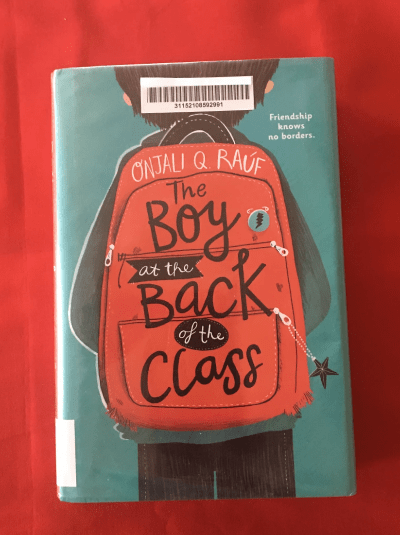

The Boy at the Back of the Class is a very gentle middle grade portrayal of a generous 9-year-old girl who makes friends with a Syrian refugee boy in her class. The boy doesn't eat lunch with the others or go to recess most days, because he's receiving counseling, and is mildly bullied, but for the most part, is highly supported by an interpreter, the girl and her three friends, and a foster-mother and school system that does its best for him. The boy has experienced the death of his younger sister at sea, during his journey to the UK, but while it's referenced in the text, her death is not explicitly shown. And he's not the main POV. He's not the narrator of his story. So his pain and trauma is filtered through 9-year-old Alexa, the girl whose POV the story features. There are small drawings, pages 98-103, depicting a plane bombing buildings, the family's trek across mountains and in a boat in the Mediterranean, with a person overboard and a speech bubble, "Help me." The boy recounts his journey to the class, but it's not graphically shown. The book could easily be used on its own in a lower elementary class, with an upper reading level of about 4th grade.

The second is a short story, New Boy, by Roddy Doyle, included in his book, The Deportees. It also features a refugee boy the same age, although this boy, Joseph, is from Africa. New Boy was also made into an excellent short film you can find on YouTube, and is commonly taught alongside the short story in high school.

What makes it YA or adult? First you'll notice the language -- there's cursing. But only four curse words, which is quite restrained for Doyle. The main character has seen untold horrors, just like the MC in the MG book mentioned above -- the difference is, in this story, the reader sees them, too. Because the boy is the narrator, the story is told from his POV. His father is murdered by fighters and the boy finds his father's body. Those images stick with him in school in the UK and are even more painful because his father was a teacher. Bullying in school is atrocious. The bully threatens him: "You're dead." And he figures out it means, "I will hurt you." The teacher does her best, but gets it wrong -- frequently -- and it's never enough to protect him. In other words, she fails him. Repeatedly. There's a girl who is kind to him, and tries to stick up for him, but neither she nor her friends are a panacea for the cruel realities of his new life.

Raúf's story is decidedly middle grade, while Doyle's is young adult or adult. It's not just graphic content that makes it so. It's a matter of voice and themes.

Raúf's themes are middle grade themes: finding one's place in school, with new friends, in a new country. Finding one's family. It's a story of belonging.

Doyle's is the exact opposite, and much more YA: forging one's own path in a cruel, brutal world. Although the main character in Doyle's story does find his place with the other kids in the end, that's not the theme. In addition, the sheer brutality the child has to endure, both at school and in watching his father murdered, is on the page. Graphically. The violence is explored. That brutality is front and center, and is a defining characteristic of the MC's voice.

The MC's voice in Raúf's is a 9-year-old girl. She serves as a filter for the reader to learn about the refugee boy's experiences and trauma. It distances the reader from the tragedy the boy has to deal with, and enables the reader to get caught up in her efforts to help him reunite with his family, as opposed to experiencing his daily struggle to handle the atrocities he's seen or his new reality.

Like a lot of middle grade, Raúf's ends on a hopeful note. There's an elaborate scheme that elicits the Queen's attention and the boy's father is located before immigration "doors" close to Syrian refugees in England.

By contrast, Doyle's story ends on a positive note as well -- he shares a laugh with his bullies in the hallway, the teacher brands them "The Three Musketeers," and they go back into the classroom together. But Doyle's is much more reserved. This is a hopeful ending for one day in school. What makes his story YA or adult is not just the foul language, or seeing the teacher's knickers, or the threats and graphic violence -- although that contributes to it -- it's the voice of the characters. There is hope, but it is mingled with infinite sadness as well.

One more "defining characteristic" of MG vs YA I'd like to explore. I see length of the manuscript get thrown around alot, also, as a definition for MG vs YA. I deliberately chose two pieces that you cannot say that about the length -- New Boy is a 12-page short story, while The Boy at the Back of the Class is 270 pages, or 56K words.

So no, the age of your protagonist does not determine whether your story is middle grade or young adult. Nor does how many words you've written.

Instead, take a look at your themes and your main character's voice and therein lies the answer to your question.